We’ve just celebrated Independence Day. Fireworks cracked the sky. Flags waved. Hot dogs sizzled on the grill. Parades marched past, brass bands playing proud and loud. And some of you may have had a fifth on the Fourth; hopefully were still able to go forth on the Fifth—but I’m glad you made it today on the Sixth!

In seriousness, maybe some of you read the Declaration of Independence again this year—those famous words: “We hold these truths to be self-evident… that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights… that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” It’s stirring. It’s foundational. It’s worth honoring.

But we’re in church today.

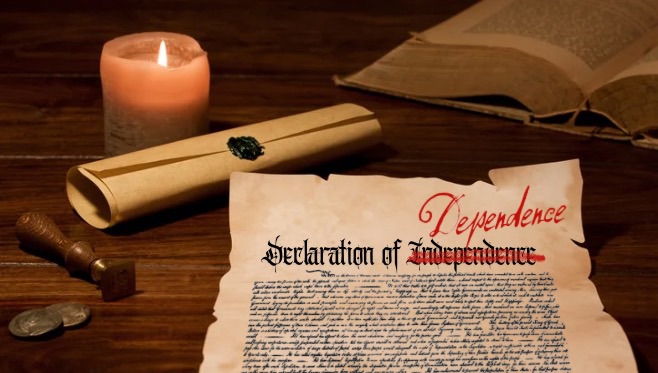

While the Declaration of Independence may have declared a new nation, Jesus declares something even more radical: a new creation. In this new creation—this kingdom of God—freedom looks different. It’s not self-reliance. It’s not having rights no one can touch. It’s not liberty that demands to be left alone. In the kingdom of God, freedom begins not with in-dependence, but with dependence.

Let’s take a look at today’s gospel. Jesus appoints seventy disciples and sends them out ahead of him, into every town and village. This is a big moment—a preview of the church’s mission. But he doesn’t give them training manuals. He doesn’t hand them money. He doesn’t even let them wear shoes. “Carry no purse, no bag, no sandals… Whatever house you enter, say first, ‘Peace to this house’… Eat what is set before you.” Wait—what? No sandals? No bag? No backup? Jesus sends them out empty-handed. He sends them not as heroes, but as guests. Not as givers, but as receivers. They are entirely dependent on the kindness of strangers. That is the shape of Christian mission.

This is where the gospel pokes at our American assumptions—especially right after a holiday that celebrates self-sufficiency and autonomy. Jesus sends disciples into the world not with tools of strength, but with a posture of vulnerability. They don’t arrive in each town with resources—they arrive in need. They have to depend on others.

And that’s not just strategy—it’s theology. Because in the reign of God, dependence isn’t failure. It’s where grace flows. We heard it in Isaiah: God promises to nourish the people like a mother comforting her child. “You shall nurse and be satisfied,” the prophet declares some roughly 750 years before the birth of Jesus. “You shall be carried on her arm… dandled on her knees.” And what kind of citizen, what kind of disciple, hears this and says, “No thanks—I can do it myself”? A faithful Christian citizen—one shaped by the gospel—recognizes that all life is shared life. Famed English poet and priest John Donne reminds us we are not made to be islands unto ourselves. We are not meant to be proud towers that never fall, never ask for help, never weep in front of others. Today Jesus calls us to go out needing others, and to not pretend we don’t.

We’ve seen this play out in everyday life. I’m thinking of the man who spent decades fixing other people’s problems, who always showed up with the right tool, the right wire, the right know-how—and then one day had to call a neighbor to help him get down the cellar stairs. Or the woman who’s been baking for funeral luncheons since the ’70s, who now receives a casserole with shaky gratitude and tears she didn’t expect. I’m thinking of the husband who always did the driving, but now sits quietly in the passenger seat while someone else—maybe even a grandkid—navigates the roads he once knew by heart. It takes courage to ask. It takes gospel-rooted humility to say, “I’m not okay. I can’t do this alone.” And when we do—when we admit our need and let ourselves be helped—we step right into the place where God can work most deeply.

That’s not weakness.

That’s gospel.

There’s a version of independence today that’s been finely curated—where life is managed by therapy apps, self-help podcasts, subscription meal plans, financial tools, and mood trackers. Everything is optimized, yet behind it all is often a quiet fear that if you need someone else, you’ve failed. The culture rewards control, and so we confuse privacy with peace. But the gospel makes a different promise. You don’t have to do this by yourself. There’s no medal for managing alone. You were made for communion, not curation. For mercy, not performance. For grace that comes from another’s hands.

Christian citizenship also means recognizing the needs of others—especially those the world would rather forget. That’s why Jesus tells them to stay where they are welcomed, to eat what is set before them, to accept the dignity of the host, even if the house is humble. The kind of Christian citizenship Jesus describes here isn’t built on self-preservation. It’s built on mutual regard, interdependence, vulnerability, and peace. It says to the other person: I need you. And you need me. And in the space between us, Christ is already working.

We’ve seen this kind of care too. We’ve seen it in the church member who brings someone to worship every week because that person doesn’t remember the way anymore but still remembers the people and the camaraderie. We’ve seen it in neighbors who snowblow each other’s driveways—not just when asked, but because they noticed it hadn’t been done yet. We’ve seen it in the woman who sits with her best friend’s husband every Friday so her friend can go to the hairdresser and feel human for a little while. These aren’t grand gestures. They’re daily mercies. They’re quiet acts of grace. They’re a kind of patriotism too—not the kind that waves a flag, but the kind that brings a plate of cookies without asking what party you belong to. The kind that says, “You’re not alone, and I’ll help carry what you’re carrying.”

Paul names this clearly in his letter to the Galatians, and a fiercely divided and polarized lot they were. “Bear one another’s burdens,” he commands, “and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ.” He doesn’t say ignore them. He doesn’t say offer vague thoughts and prayers. He says bear them. Carry them. Take them on yourself, like you would a pack on a weary friend’s back. Because we’re not just individuals living near each other—we’re a family of faith. And Paul goes still further, saying, “Whenever we have opportunity, let us work for the good of all.” That’s what Christian citizenship looks like. Not just voting or waving a flag for your political team, but working for the good of all, especially those whose needs are easiest to overlook. A Christian citizen doesn’t ask what someone else should do for them, but asks themselves what they can do for someone else.

Our virtual world is shaping our real world. Online platforms shape hearts, opinions, priorities. They can inform and awaken. But we cannot confuse what we do in our virtual relationships with the fullness of what Christ calls us to live in flesh and blood. Neither airing grievances nor calling for justice online is sufficient in its own right to satisfy the depth of the embodied gospel Jesus calls us to live. He doesn’t send us to proclaim from a platform. He sends us house to house. In person. Where we’re asked to receive someone’s hospitality, not just share a headline, soundbite, or tweet. He sends us where we speak peace, not with curated clarity, but with dusty feet and open hands. There is no such thing as click-based discipleship. The kingdom is near not in theory, but in bread, bodies, and neighbors who share burdens.

We don’t always know when we’ll be the one in need. That time may come when the furnace breaks in the middle of February, and the phone call you make is to your grown child because you just can’t figure it out on your own. It may come when the medication bottle is suddenly too hard to open, or when your calendar is empty except for doctor appointments. It may come when you realize you can’t make it through the grocery store without leaning on the cart for more than balance. And when that time comes, the last thing Jesus wants you to feel is shame. He doesn’t say, “Figure it out.” He says, “Take nothing. Be received. Speak peace. Let yourself be fed.”

The gospel does not scold us for depending on others.

The gospel honors it.

That kind of life—burden-sharing life, interdependent life—means we’ve got to let go of pride. We can’t pretend we’ve got it all figured out. We can’t be so proud in ourselves that we hide our own need. The minute we start thinking we’re self-made, Jesus sends us out again—empty-handed, unarmed, and dependent. Because that’s where the Spirit begins. When we can say: I don’t have what I need. I can’t do this by myself. I am sent not in strength but in need. That is when God does holy work.

This morning, Jesus doesn’t hand us the Declaration of Independence. He hands us bread. He hands us wine. He hands us himself. And he says: You need this. You can’t do this alone. Take. Eat. Drink. Let someone else feed you. This table isn’t a prize for the righteous. It’s a meal for the dependent. And this meal is our Declaration of Dependence.

So yes, we give thanks for the country we live in. We pray for its leaders. We remember the blessings of freedom. But we also remember this: Our truest freedom begins when we stop trying to be free from God… and start living freely with God. In the kingdom of God, we are free to need. Free to depend. Free to bear and be borne. Free to recognize the needs of others. Free to admit our own needs. Free to live not alone, but as a people redeemed, connected, and loved.

You are not alone. You are not expected to be enough. You are not called to carry this gospel solo. You are sent, and fed, and sustained—by God and his people, Jesus’ own body still alive and well in every corner of the world to this day.

That is our Declaration. That is our Freedom. Thanks be to God. Amen.