Resurrection changes everything. It has to. You can’t rise and stay the same. When Christ walks out of the tomb, the world tilts. What was certain shatters. What was impossible happens. That’s why Lent isn’t just a season—it’s preparation. We strip away dead weight, what holds us down. We turn around, realign. That’s Lent’s repentance—death to what stands against God’s will in our lives and death to our hand in what opposes God’s will in the world. Resurrection is God’s victory over that. It’s the breaking of chains, the undoing of every force that resists his will. But for something new to rise, the old must die. So when the stone rolls away, will you rise—or cling to what should die?

Let us pray.

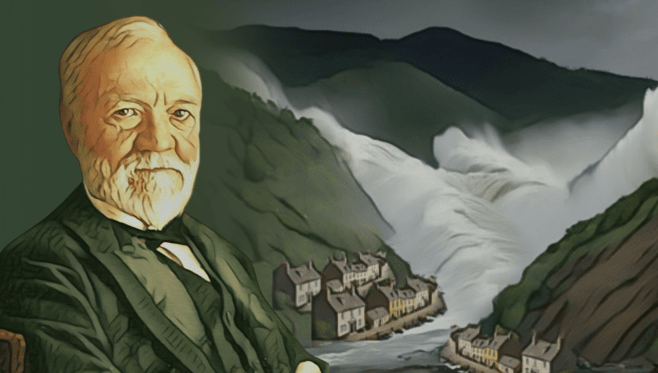

May 31, 1889.

A very rainy day in western Pennsylvania, the heaviest rainfall event that’d ever been recorded in that part of the United States to date, in fact. Yet the unsuspecting townspeople went about their routines, unaware that miles upstream, Lake Conemaugh was rising against the South Fork Dam. By midafternoon, heavy rains had weakened it. At 3:10 p.m., the dam failed.

What followed couldn’t be stopped.

A wall of water, 40 miles an hour, thundered down the valley toward Johnstown. Trees, homes, railcars—entire neighborhoods—swept away in minutes.

Some ran. Some climbed. Others, frozen in disbelief, were swallowed whole.

Over 2200 dead.

The worst loss of civilian lives in the United States in a single day until September 11, 2001…

But this wasn’t just a natural disaster. The flood bore human fingerprints.

The dam had been neglected. Built decades earlier, it had fallen into disrepair until a group of wealthy industrialists bought it for their private club. They lowered it for a carriage road, removed drainage pipes, ignored safety.

Warnings came. Engineers raised alarms. But the dam stood—until it didn’t. The flood that destroyed Johnstown was born of privilege and carelessness. Men enjoyed their retreat while thousands below trusted the structure would hold.

Andrew Carnegie was one of them. A titan of industry, self-made, risen from Scottish poverty to American wealth. He and his peers enjoyed their sanctuary high above Johnstown, feasting while workers below toiled in mills and factories, earning scraps.

Warnings didn’t move them. Their concerns were profit, not people. The dam was a backdrop to their leisure, not a responsibility. The people below weren’t their concern.

So when the waters came, they came not just as flood, but as judgment—a reckoning for the arrogance that thought power stood immune from consequence.

Millennia earlier, another people stood on the edge. The Israelites had seen their world fall. Jerusalem, leveled by the pompous, idolatrous, foreign Nebuchadnezzar. The temple, destroyed. They were exiled, miles from home among the pantheomiscuous Babylonians. Everything they knew—gone.

Yet God spoke through Isaiah: “Do not remember the former things…I am about to do a new thing. Now it springs forth—do you not perceive it?”

At first, it sounds insensitive. How could they forget? Their city and temple were gone. But God wasn’t asking them to erase the past—he was calling them to stop longing for it and trust what he would do next.

This wasn’t just return—it was renewal. The exile wasn’t just political; it was theological. Israel believed they were chosen—through Abraham, Moses, David. But now? No land, no temple. Had God left them? Was the covenant broken?

Isaiah says no. Exile isn’t the end. The covenant isn’t destroyed—it’s transformed. They wouldn’t just go back. God was doing something new. The exile stripped away illusions of security, but in that desolation, God prepared them for deeper faith. A relationship not bound to place or building, but to God’s promise. The question wasn’t if they could restore what was—but whether they could trust what God was building next.

When the flood comes, we have two choices: cling to the wreckage or step into what God is doing.

Renewal isn’t a return. It’s something new—unfamiliar, even unsettling. Just as Johnstown could never be rebuilt as before, and Israel’s future wouldn’t mirror its past, God’s work isn’t reconstitution—it’s transformation.

That’s the heart of our faith. God doesn’t simply restore what was. He renews. He transforms. St. Paul knew this. In Philippians, he counts everything that might make him somebody as loss compared to knowing Christ. His status, achievements, identity—none matter beside what God is doing. And in John’s gospel, Mary pours perfume at Jesus’ feet, preparing him not as the we’d expect, but for what was to come. Both knew what Isaiah proclaimed: when God acts, the old ways, old values, old assumptions—none hold. God is doing something new.

He could’ve done what others did—deny, deflect, move on, leave Johnstown in ruins.

But Carnegie didn’t.

Something shifted. He’d always been ruthless, but after the flood, he redirected his fortune. The disaster became a turning point—toward philanthropy.

He poured funds into rebuilding. A new library in Johnstown—one of many to come in other cities. His vision expanded: museums, institutions, concert halls—even Carnegie Hall in New York. The flood reshaped his legacy.

Like Paul. Like Mary. Carnegie let go of the old and embraced the new.

We all experience floods—not always literal, but emotional, relational, spiritual. We lose what we thought we couldn’t live without. The scaffolding collapses. Life—changed.

In those moments, we choose.

Do we cling to what was? Rebuild the past, brick by brick? Or trust that God is doing something new?

Maybe it’s realizing the old path to success—work hard, save, retire—doesn’t hold anymore. Jobs lack pensions. Housing costs soar. Security feels like a myth. But what if success isn’t wealth or status, but relationships, wisdom, meaning?

Maybe the church you loved is changing. Attendance drops. Traditions fade. The temptation is to cling tighter. But what if the future isn’t in preserving the past, but making space for what God is doing now?

Or maybe your role is shifting. Strength fades. Time feels faster. It’s tempting to grieve what’s lost. But what if this moment is a new calling? What if wisdom earned is meant to be shared?

God’s renewal isn’t a rewind. It’s something new. Just as Johnstown couldn’t be rebuilt exactly, and Israel’s future was not a replica, transformation is not reconstitution—it’s resurrection. Buried with Jesus in baptism, we are raised in newness of life.

This is the heart of our faith. God doesn’t restore the past—he renews it. Transforms it. Paul knew this. Mary knew this. Isaiah knew this.

Carnegie didn’t walk away. He was changed. The flood became his turning point.

Like Paul. Like Mary. Carnegie embraced the new.

And so must we.

We all face floods. We all stand on the banks, watching the waters rise. The world shifts. But Isaiah still speaks: God is doing something new. Do you perceive it?

Lent is a time to perceive it. A season of baptismal renewal, dying and rising with Christ. A season to get honest about the ways we cling to popular wisdom. Lent should unsettle us. It should remind us: resurrection requires death. And baptism means new life.

God’s renewal isn’t always gentle. It often feels like wreckage. But through the flood, through the loss, God makes a path. His mission isn’t to rebuild our past—it’s to reshape the future. To make all things new.

Even us.

Even you.